Arthur, a janitor at Hollow Press, was nearing the end of his shift—or perhaps somewhere in the middle. He didn’t tell time by clocks. Arthur had his own way of telling time. Belly gurgles and the strength of hunger pangs were his hour and minute hand. The downside being a day like today, when a misplaced mop bucket led to a spill that could have easily been mistaken for Moonshadow Pond. Arthur was forced to skip lunch to get the mess properly dealt with and leaving his internal Rolex wildly off the mark. Knowing he only had a few more offices to tend to, he pushed through. Doing his best to ignore the gnawing in his stomach.

Arthur’s a short, stout fellow. Hands calloused and weathered, the hallmark of a lifetime spent working hard. His fingers are in a permanent semi-circular shape from gripping cleaning instruments on long sticks. A proud man with an impeccable work ethic, HR wouldn’t be able to find a sick day or vacation request in their files if they tried. On time each morning, his work is completed before he leaves every evening. That’s not to say he is well liked or an agreeable fellow, but certainly committed to doing his job the right way. His faded dungarees barely hanging onto his hips, kept up only by suspenders that threaten to give out at any moment.

As he approached the next room, the one in the editing wing with a sign on the door that read: Tiny McTurdPolisher, Senior Editor. He grabbed for his keys that hung heavy from the waistband of his pants. A keyring so heavy, they were the likely cause of his suspenders struggling to keep its threads intact. He unlocked the door and entered, carrying a broom, a rag and a spray bottle of cleaner. On the wall was a mossboard with two notes pinned there. One note read, Deadline: Already passed. The other read, 400,000 words will never sell. Commence Operation: Waste Wood. Arthur vaguely recalled hearing the term used one or twice in the past and judging by all the parchment scraps littering the floor, he assumed that meant this McTurdPolisher fellow had the task of cutting out a whole bunch of words. Arthur was one of those people that knew the goings on at Hollow Press better than just about anyone else. He wasn’t just good at his job, he was also perceptive. Using his eyes and ears to keep tabs on things.

He knew there was a big-time author being paid big money to put out a series. A series that could put Hollow Press in a whole new league in the publishing world. From what Arthur has pieced together, this still untitled work was expected to do very well, but given this new information on the mossboard — seems as though things are not going as hoped. Besides the apparent timeline and manuscript girth issues, he’d heard the author was prone to over-analyzing every little detail and also a bit of a diva. Arthur went to work, not giving any thought to whether or not the paper on the ground should be left right where it is. His motto has always been, “If you don’t want it tossed, put it in an appropriate place.” The floor was not one of those places. Amid small fragments of aggressively ripped up parchment, Arthur saw two larger pieces. He picked them up, reading their contents. He burst out in laughter as he read both strips. Sure there was a bit missing from the middle, but it made enough sense that he found his chuckling automatic. Now Arthur is not known around the office for his sense of humor, the mistake of assumptions. Arthur was not humorless, rather he expressed less of a humorous side than most. Jimmy, one of the younger crew members, heard the cackling from down the hall and came to investigate. Pushing the door open, he did not expect to see Arthur standing there giggling and holding pieces of paper.

“What’s so funny?” Jimmy asked.

“Mind yer business.”

Jimmy paused, shrugged and then moved on. He knew better than to try having a conversation with Arthur. Arthur was the kind of guy you gave a single upward nod and grunt a half a Hey to and be happy if he even looked. Still, Jimmy wondered what could have been funny enough to cause Arthur (of all people) to roar as he did. Sadly, Jimmy would have to wait a long time for an answer to that thought.

Arthur neatly folded the two pieces together and stuffed them in his pocket. Patting his pocket he thought, “This could be my retirement. If the book ends up doing well.” His plan was simple:

- Hide the pieces of paper.

- Hope the book ends up being a huge success

- Sell the scraps to the highest bidder

Arthur always has a retirement plan in mind. Everyday after work, he stopped by the QuickMud Mart for a Meadowsweet soda and 2 lichen scratchers. He’d tell anyone interested that he was going to hit it big on a scratcher someday and then he could retire — moving to the nicer side of the bog.

His wife, Lucy, would kiss him sweetly when she saw the disappointment of another dud ticket. Telling him softly, “One day Arthur. One day.” Of course she didn’t give him any grief over wasting money. She knew he earned every card he played and all the dreams that came and went with them. Oh how she wished for his dream to come true, if only to see the sparkle she saw in him 40 years ago.

That day, he didn’t sit in his favorite chair after leaving his shoes by the door and changing out of his work clothes. Lucy was a stickler for a tidy house. No, that day he headed straight for the attic to find the perfect spot to hide his winning tickets.

Years had passed before that hit novel was published, something about a disagreement with the author that was eventually sorted behind closed doors — in hushed meetings. The novel went on to be a huge success, bringing with it the outcome of the hopes Hollow Press has placed on the piece. By then, Arthur had already retired and had forgotten all about his winning ticket. Truth is, his house was littered with winning tickets. He frequently snuck bits of Hollow Press property home with him. Convinced each one would be the one.

Lucy passed first. Arthur followed not long after. A gentleman purchased a chest from the estate sale of one Arthur Cobblepot. In the chest, he found two pieces of paper. Initially deciding they were nothing more than a bit of lining from the chest drawer, until he noticed on the back of one was scribbled Winning Ticket. His curiosity piqued, he began asking around about this Arthur Cobblepot character. It was during one of his fact finding quests down at Bitterroot Tavern that he happened upon a fellow named Jimmy. Jimmy took a look at the pieces of paper and confirmed they might be the pieces of paper he saw Arthur holding while laughing, all those years ago. The man, having read the pieces, understood the laughter. Jimmy told the man that he and Arthur worked together at Hollow Press and that is where he saw Arthur with the fragments.

The man took the fragments to Hollow Press, hoping to discover anything at all about them. One of the copy editors, figuring out the possible timeline of events, suggested he talk with the now retired Tiny McTurdPolisher. The man did just that. Tiny’s eyes went wide as he looked at the pieces. Yep, I know them. I was the one that ripped them up. Tiny recounted the story of the novel he’d been tasked with trimming. Tiny paused, chuckling to himself, that wasn’t trimming. That was a hack and slash job. Tiny asked the man what he was going to do with the pieces. “I think I will just scrapbook them, now that I know the backstory.” — that was a lie. The man intended to go back to Hollow Press with everything he knew and give them the opportunity to offer a price before he took them to the open market. The executives and law team at Hollow Press knew they could win an intellectual property and copyright right case in court, but also knew it would cost them. Deciding instead to offer something below what they thought they would have to spend in court. Making an offer, low-balling it to disguise just how badly they wanted those pieces back. The man took their offer and disappeared. The settlement was never disclosed but according to the Hollow rumor mill, made up mostly of the ladies down at Color & Cut Beauty Salon, the payment was twenty-five thousand Glimmercap mushrooms and a coupon for a lifetime supply of Pop-Beetles down a Mossplex 8. It was a place you’d find the kids watching the next action flick on Lichen screens. A place where the smell of caramel covered Pop-Beetles was definitely NOT (yes it was) wafted across the pond, propelled by the wings of Dragonfly Squadron Alpha, who were contracting for prime landing spots among the reeds.

One might think the contents of those scraps—the ones that made Arthur laugh so hard—would remain a secret.

But a nosy frog caught wind of the goings-on, perched at the tavern bar like a fly on the wall.

He saw the parchment as the man held it—some traveler who vanished not long after collecting his prize—and, gods help us, committed the words to memory.

You can thank Taddle for what you’re about to read.

(Though I wouldn’t trust he remembered the words correctly.)

###

* Found on the first parchment piece *

Scene Fragment: “The Brownie Incident”

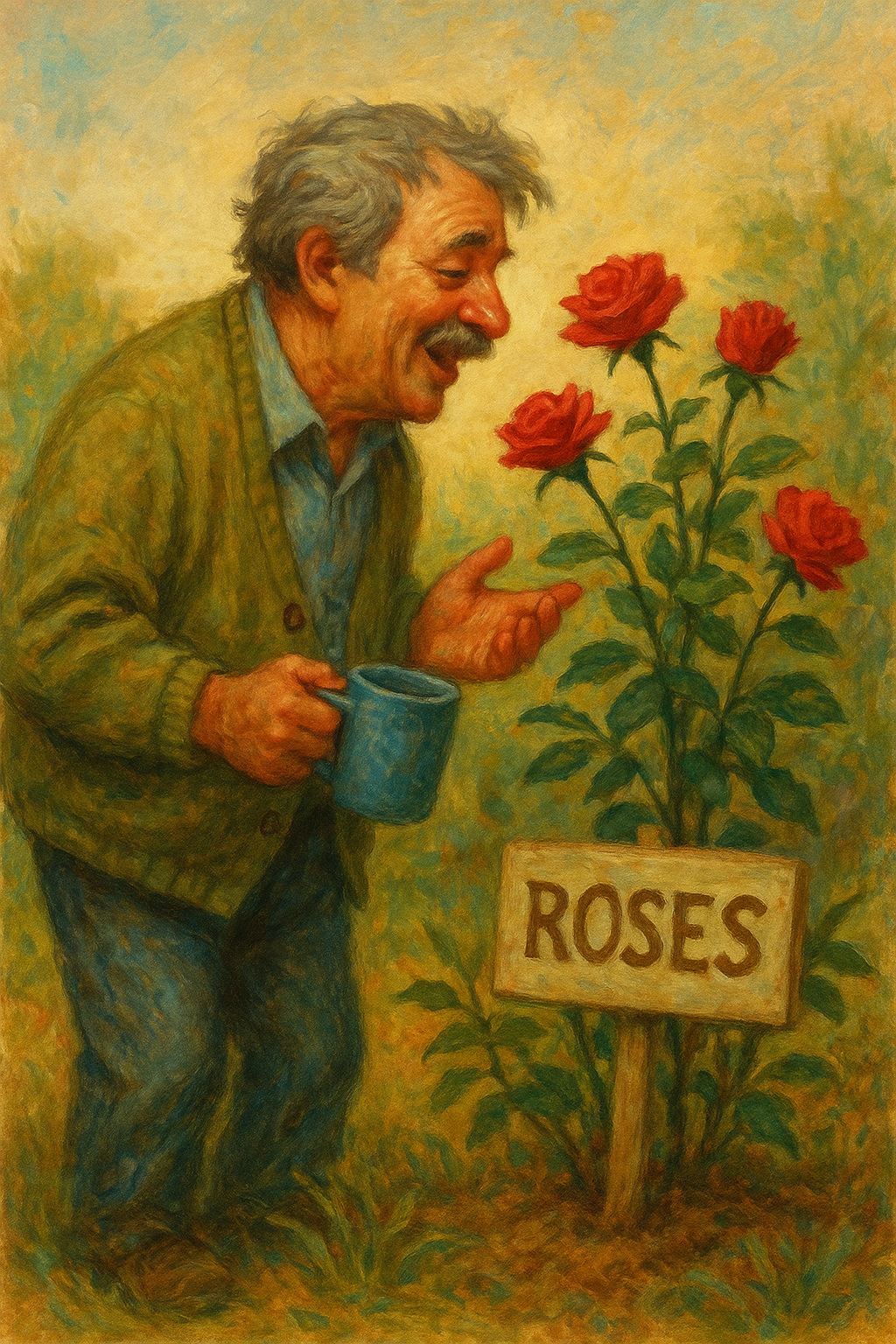

Mary squints through the kitchen blinds, clutching her coffee like it might explain something.

Out by the shed, Bob is talking to the rose bush. Not at it. To it.

His arms are moving in slow, circular gestures. He’s smiling.

He is not weeding.

Mary (half to herself):

“I could’ve sworn the sign said gluten-free…”

Just then, Richard walks in with that patented my-mother-has-done-it-again expression.

Richard: “Oh, Mom.”

(beat)

“Please tell me you didn’t buy something from those kids outside the store again.”

Mary (defensive): “They were wearing matching shirts!”

Richard: “So was the Manson family.”

(Outside, Bob is now offering gardening advice to the cosmos. He’s calling the rose bush David.)

###

* Found on the second parchment piece *

clutching receipt paper like it’s a notary stamp, swearing up and down that yes, those brownies said “GLUTEN FREE” and no, she didn’t notice the cartoon mushroom riding a rainbow on the label.

Mary: “They said it was for a music program.”

Richard: “Yeah. The one in their heads, Mom.”

And still, somehow, she’ll defend those teens until the day she dies:

Mary (weeks later): “That one boy had such kind eyes.”

Richard: “He had pupils the size of dinner plates.”

Mary: “I just thought he was excited about music.”